Investing in energy is tricky as the sector follows supply and demand cycles. Opportunities to buy with solid protection from risk are rare. Uranium is interesting since it embodies the best advantages of commodities while possessing many associated risks.

An analysis of the uranium supply/demand situation is needed to explain why Cameco is such an intriguing investing opportunity. In 2021, nuclear producers produced 155 million pounds of uranium, 125 million pounds from operations (i.e., literal mining and extraction), and 30 million pounds from the secondary supply. Secondary supply comes from many sources: excess material from old military weapons, uranium held in Sprott (an investment vehicle that buys and stores uranium before reselling for profit), and underfeeding. Underfeeding in its technical definition is complicated, but its implication for the uranium supply is quite simple: more enriched uranium is produced than mined. Instead of putting 1 lb of uranium for 1 lb of enriched uranium, enrichment facilities, due to low demand, can enrich uranium longer and cause 1lb of uranium to yield 1.5 lb of uranium. Trade tech estimates that 200 million pounds of uranium are demanded, while the world uranium organization estimates the demand to be at 187 million pounds, creating a demand gap. Cameco and Kazatomprom’s supply discipline has worked: market prices for uranium are ticking up (though still below the $55-60 cost of production). It will likely tick higher until major producers increase production. Another factor is further widening the supply-demand gap: Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. As a result, Russian enrichment facilities have been sanctioned, pushing extra demand pressure on Western enrichment facilities, leading to overfeeding. In short, a lack of enrichment facilities further exacerbates the supply gap, in the best-case scenario, roughly 20 million pounds (a bit of oversupply starting + under-supply ending + warhead and alternative supplies) on top of the 45 million from supply discipline. No matter how you look at it, there is room for prices to rise accordingly.

Cameco is a strong company well-positioned to take advantage of this situation. First, they are the only western publicly traded uranium “producer” (companies with certified deposits of uranium). They account for 18% of global production and use that to their advantage: since 2016, Cameco has been withdrawing 30 million pounds of uranium annually to create the supply gap. For context, their business model is quite simple, Cameco mines and refines uranium before selling them to utilities. In economics, they call it “inelastic” demand. Power plants need uranium; there is no other fuel alternative, so they would pay any price.

Second, they have tied 170 million pounds under long-term contracts for the next five years, meaning, on average, assuming uranium spot prices fall to $40. If Cameco ceases to conduct contracts, they would have 1.3 billion dollars for five years. (around 92% profit in 2019 for context). Third, energy companies usually run with high debt because of capital expenditure and other operational costs; Cameco is no exception. Total debt is around 1 billion, with 0.5 billion due in 2024; Cameco is well positioned to repay its obligations: it has roughly 3.5 billion in liquid assets. If worse comes to worst, it is highly protected, the bottom line being Cameco can consistently generate cash while having the buffers to stay afloat for a decent amount of time. Its recent acquisition of Westinghouse is another positive: Cameco’s development of a total value nuclear chain will allow it greater flexibility over prices, enrichment, and production. (think standard oil but for nuclear power)

Cameco does have its concerns; however, the general margins are slightly concerning, collectively EBITDA, Gross and Net margins have declined by 7.5% per category. From my understanding, a lot of it is influenced by supply discipline – it is more expensive to maintain low operating uranium mines than uranium mines at regular or higher capacity. Furthermore, this decline also coincides with lower total revenue from weakening uranium prices; perhaps a sign that lowering margins wasn’t entirely management’s fault. While the financials are better this year (gross profit, EBITDA and net margins are all higher), the concern is obviously still present – what if uranium prices fall again? Obviously concerns like Fukushima and government oversight are there as well.

Cameco looks positive regarding both short- and long-term growth. The uranium sector in 5 years can expand because of the economics of the supply gap and in 10-15 years could genuinely enlarge due to demands for alternative energy in combating climate change.

Sometimes there comes an investment that looks too good to be true and Cameco, to me, is an example of that company. It is an extremely important producer – the only publicly traded western producer – and the management has crafted an ambitious strategy backed with strong financials. The risks are there, like with any commodity/energy stock, the company is heavily tied to the price of the commodity and Cameco is no exception.

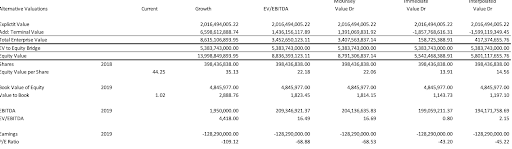

To conclude, below is my valuation of the company; note that the lower valuations assume that the company loses cash nonstop for the 10 years that I project. Also, I did not model uranium prices, which would accentuate Cameco’s profit in either direction. To sum up, Cameco’s long-term prospects, as it is closely tied with the price of uranium: from higher estimates of 35 to low estimates of 14.56.